Today’s project is collages! No scissors and glue, but we’ve got the next best things: REST APIs and the Python Image Library. Specifically, we’ll be accessing card illustrations via the shiny new(ish) Scryfall API, working a bit of magic on them, then stitching them together.

This is all based on some work by a friend-of-a-friend, April King. She put together a collage of Island illustrations, earning herself a shout-out in the Scryfall blog. We’ll be starting with her same idea, then taking it a bit further.

Getting Images

Working with the Scryfall API is a breeze. You ping a URL, and you get back a conveniently-formatted reply. For example, let’s say we want to search for all 500+ printings of the card [[Forest]]. After a quick peek at the Scryfall search syntax guide, we type a few lines of Python and have all that information at our fingertips:

import requests

# The query !"forest" gets cards named exactly "forest".

url = 'https://api.scryfall.com/cards/search?q=!"forest"&unique=prints'

forest_info = requests.get(url).json()

If we go to the the above URL ourselves, we see a jumble of JSON. Some snippets of relevant-looking information, but condensed to the point of illegibility. Python gobbles that up no problem and spits out a well-behaved dictionary. Card data (rules text, collector number, etc) is packaged in forest_info['data']. In this case, there are too many search results to fit on one page, so forest_info['next_page'] tells us where to make another request for the next batch.

To see more details about working with the API, feel free to check out my code on GitHub. Long story short, we grab just a few pieces of information from Scryfall:

- Set and collector number to uniquely identify each card

- Artist name – more on this in a moment

- The URL where they store the illustration

We make another API request to grab the illustrations and dump1 each into a file. From there it’s easy enough to load them up, crop them to a common size, and toss them together into a collage:

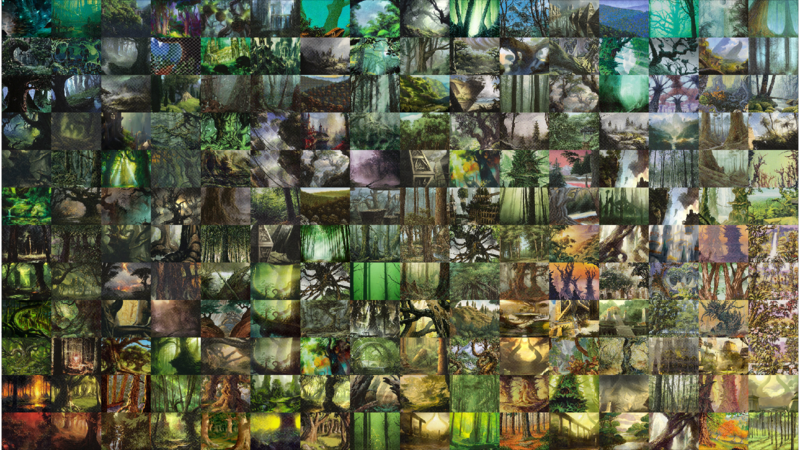

All 587 Forest illustrations, in the order Scryfall returns them. A number of duplicates are visible. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

All 587 Forest illustrations, in the order Scryfall returns them. A number of duplicates are visible. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

There have been 587 printings of the card [[Forest]]. The above collage includes them all. Looks alright, I guess, but something feels off…

Identifying Duplicates

Just because each basic land has been printed over 500 times doesn’t mean there are 500 different pieces of art. A handful of pieces appear repeatedly – particularly in the promotional releases on the right side of the collage above. I set out to remove the duplicates. Turns out that’s easier said than done2.

It’s trivial to check if images are pixel-by-pixel identical, but that’s not the situation here. We’re looking at different scans of the same original piece of art. That means slight differences in cropping and exposure, plus perhaps some digital retouching.

The correct way to solve this problem probably involves machine learning, neural networks, or some other big data buzzword. A bit beyond my expertise, and a bit overkill for this particular project. Instead, after a fair amount of trial-and-error, I essentially decided to identify duplicates by squinting:

- Convert color images to grayscale.

- Scale down to a coarse grid.

- To compare two images, subtract their grids.

- If the differences are uniformly small, the images match.

The figure below shows how this process plays out. It correctly matches a pair of pieces by Alayna Danner, one of which has a weird foil overlay. And it correctly distinguishes a pair of pieces by John Avon, despite their similarities.

Illustration of how the matching algorithm works. It can identify a match despite the weird foil overlay. It can also distinguish a pair of pieces with similar color scheme and composition.

Illustration of how the matching algorithm works. It can identify a match despite the weird foil overlay. It can also distinguish a pair of pieces with similar color scheme and composition.

The above figure uses a 4x4 grid for legibility; in practice, the sweet spot seems to be 6x6. If the grid is too tight, the algorithm is easily confused by differences in cropping. If it’s too coarse, distinctive features are often lost, resulting in false positives.

That said, no matter how well we dial in the grid, it bears noting that this is a pretty good algorithm for identifying duplicate images – not a perfect one. In particular, it gets confused when artists do [[269629:throwback]] [[245246:pieces]]. We won’t be filing any patents, but it works well enough to reduce our 500+ printings down to about 200 mostly-unique ones:

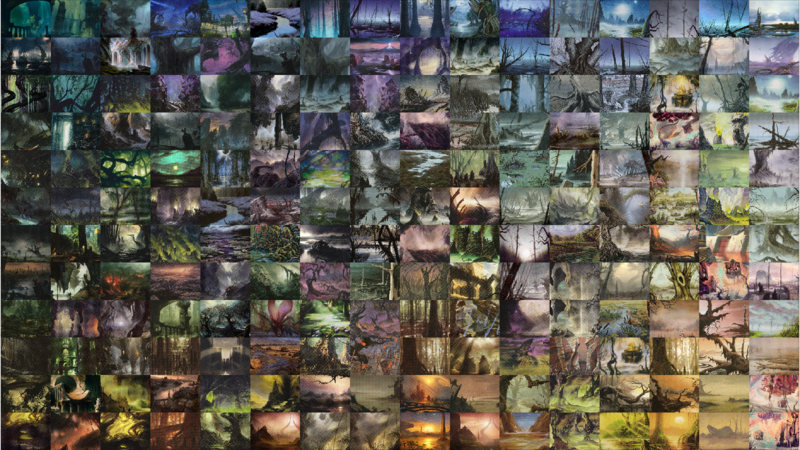

Collage of [[Forest]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Forest]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Optimizations

The matching algorithm only handles pairwise comparisons. That means, to find all the duplicates in a pool of 587 images by brute force, we’d need to make 172k comparisons3. That’s how I coded it up the first time through, and it slowed my little netbook to a crawl. Eventually, I realized that there was a huge optimization staring me in the face: artist name! If we have a piece by Alayna Danner and another by Jim Nelson, we already know they’re different. No math required.

Rob Alexander has art on 44 [[Forest]] printings, so it takes 946 comparisons to find all the duplicates. Terese Nielsen has five illustrations, so that’s another ten comparisons. All in all, 71 defferent artists are credited on Forests, and it takes about 12k comparisons to identify all the duplicates for all of them – less than a tenth of what we would have to do using brute force! On my machine, I can load up all the images, purge the duplicates, and assemble a canvas in about a minute.

Of course, I don’t load all the images at the same time – that’s my other optimization. More than once, the OS killed my Python script for being too much of a memory hog. So now I’m more careful with resources.

Each image gets loaded once at the beginning to grab some metadata. We store image dimensions, plus we compute the grid of grayscale values for the matching algorithm. While we’re at it, we crunch out the average color for each image as well. Then we free up that memory – keeping only the metadata – and load the next one.

Collage of [[Island]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Island]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Once we have metadata for each image, we use the grayscale grids to identify duplicates. Based on the number of unique images, we can then figure out an appropriate number of rows and columns for the collage. And, with each illustration’s dimensions, we can compute a common size to crop to. Then we go back and – one at a time – load the images again. Each gets resized, cropped to the appropriate aspect ratio, and slapped onto the canvas.

Finishing Touches

Scryfall orders search results chronologically, which is very practical, but practicality isn’t really what we’re after. Personally, I think it’s sharper to have illustrations ordered by average color instead. From left to right, the illustrations in each collage go dark to light. Then, within each row, they’re sorted from red to blue. For the [[Forest]] art above, it doesn’t make much of a difference. It’s all green. Similarly, the [[Island]] collage is all blue, and the [[Swamp]] collage is all brown and purple:

Collage of [[Swamp]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Swamp]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

But the [[Plains]] and [[Mountain]] collages are a whole different story. In each, there’s a visible transition between the warm colors of the earth and the cool blue of the sky.

Collage of [[Plains]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Plains]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Mountain]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Collage of [[Mountain]] illustrations. Duplicates removed. Full-sized version here, art credits here.

Sometimes, art is more art than science. Sometimes it’s not!

-

If you’re actually wading through the code, you’ll notice that dumping the image to a file is actually a multi-stage process. The images served by Scryfall are formatted as JPGs. We’d rather work with PNGs, so we do a quick check-and-convert. ↩

-

As it turns out, Scryfall flags duplicate illustrations via the illustration ID. But that takes all the fun out of it! ↩

-

The number of ways to choose two different items from a pool of N items is N*(N-1)/2, also called “N choose 2.” ↩