In Amonkhet draft, the fastest decks are wildly aggressive. Slower decks have access to powerful synergies; embalm, -1/-1 counters, and trial/cartouche shenanigans all offer viable lategame plans that don’t rely on opening a bomb rare. The unusually-broad format, combined with the return of cycling, has prompted many to move away from the 17-land conventional wisdom for a draft deck. There are rumblings of people running land counts as low as 14.

Fewer lands means more spells, and it’s spells that win games. We all know the frustration of watching a game slip away while topdecking land after land after land. But a low land count presents a liability as well. Missing an early land drop can be backbreaking, especially against an aggressive opponent.

Optimizing your land count is one of those things that’s hard to do by feel – it takes a lot of work to differentiate between problems with your deck and problems with your luck – so let’s crunch some numbers. We can use combinatorics to go from land counts to probabilities (see footnote1 for more details) but first let’s quantify exactly what sort of draws we’re looking for:

- Even when playing a very aggressive deck, we want to hit our first 3 land drops. This gives us the resources to remove blockers while continuing to build our board – either by casting multiple spells per turn or by deploying heavy hitters like Ahn-Crop Crasher and Cartouche of Ambition. A few more lands is fine, but if we have 7 lands on turn 7 we’re definitely flooding. So let’s look at how different deck configurations affect our odds of having at least 3 lands on turn 3, and at most 6 lands on turn 7.

- For a midrange deck, we want 4 lands on turn 4. We’re happy to play Colossapede on curve, then Winged Shepherd, then maybe even Greater Sandwurm… but if we hit 8 lands on turn 8, we’re probably running out of gas. So let’s also look at the odds of having at least 4 lands on turn 4, and at most 7 lands on turn 8.

- Finally, let’s look at how land count and cycling affect the odds of having at least 5 lands on turn 5, and at most 8 lands on turn 9. This would apply to a deck which has trouble winning without a prompt 5-drop – Decimator Beetle, Final Reward, Angel of Sanctions, Glyph Keeper, etc.

In order to include cycling in our analysis, we need to make a quick simplifying assumption. Let’s assume we cycle every cycler2 as soon as we draw it. This assumption is imperfect – we’ll come back to it later – but it makes our bookkeeping a lot more manageable. This way, we can simply treat a 40-card deck with 4 cyclers as a 36-card deck.

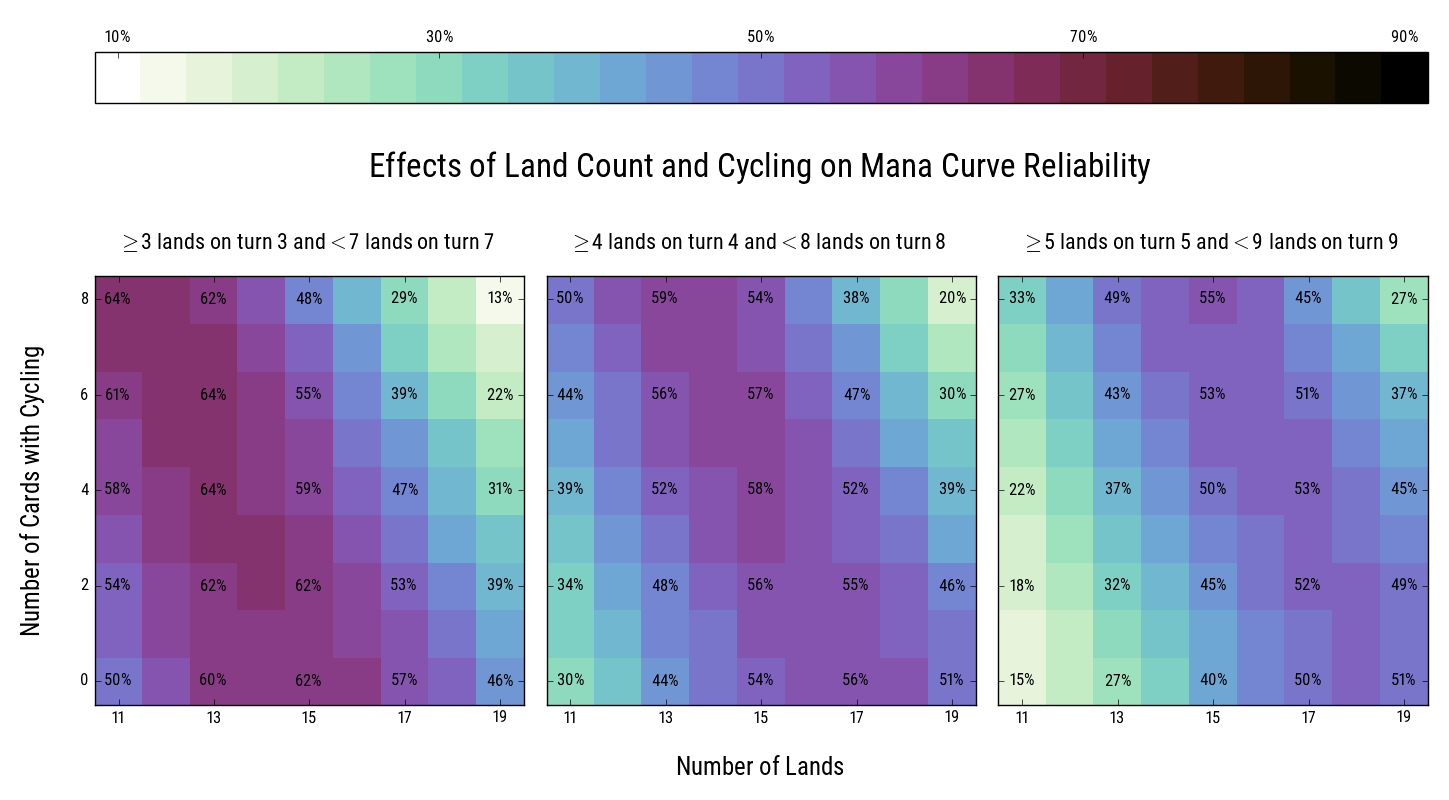

The resulting probabilities are shown in the figure below. There’s a lot of information to unpack; let’s talk through it.

The above plots show the odds of drawing a “good” number of lands, based on the deck’s number of lands and the number of cards with cycling. The left plot applies to an aggressive curve, the center plot to a midrange deck, and the right plot to a slow deck. See larger version here.

The above plots show the odds of drawing a “good” number of lands, based on the deck’s number of lands and the number of cards with cycling. The left plot applies to an aggressive curve, the center plot to a midrange deck, and the right plot to a slow deck. See larger version here.

The center plot shows the odds that we’ll draw a “good” number of lands for a midrange deck – at least 4 lands on turn 4, and at most 7 lands on turn 8 – depending on land count and cycler count. With no cyclers, the sweet spot is at 17 lands, in line with the conventional wisdom. With fewer lands than that, the risk of missing land drops starts to outweigh the danger of flooding, and vice versa. Every time we add 2 cards with cycling, our ideal land count drops by 1. With 4 cyclers, the plot suggests our midrange deck can get away with 15 lands; with 8 cyclers, it says we could play just 13!

We see a similar trend with the plots on the left and the right. If the 3rd land drop is the last one we need to hit reliably, 15 lands is about enough, even without cyclers to smooth out our draws. That may be believable… but 11 lands and 8 cyclers is not.

The issue is, we’re running into our simplifying assumption. With an 11-land deck and 8 cyclers, we’re 64% to hit our first 3 land drops. A 15-land deck with no cyclers gives us similar odds to hit those land drops. But that doesn’t mean those decks are equally likely to curve 1-drop into 2-drop into 3-drop. An 11-land deck with no cyclers is only 50% to hit those land drops. The 14% difference comes from games where we have to cycle something – likely disrupting our curve – to find land.

There’s a more subtle caveat we should touch on as well: maximizing the odds of drawing a “good” number of lands may not be the same as maximizing the odds of winning. Our midrange deck (with no cyclers) will draw the a “good” number of lands about 55% of the time, regardless of whether it plays 15, 16, 17, or 18 lands. That means we need to consider what we want the other 45% of games to look like. We might play 16 if we’ve got a bunch of Naga Vitalists, Dune Beetles, and Magma Sprays to help us stabilize after stumbling on lands. If we can handle too many lands better than too few – maybe we’re playing Seeker of Insight or splashing a third color – we might go with 18 lands instead.

Ultimately, no matter how many lands we play, we’ll sometimes lose games due to flooding. We’ll also sometimes lose due to missing early land drops. The above analysis can’t make those dangers disappear, but it can help us understand them (and perhaps balance them against one another):

- Playing 15/17/18 lands maximizes our chances of hitting 3/4/5 land drops without flooding up to 7/8/9.

- Adding or removing a land barely affects our odds of drawing a “good” number of lands. It mostly affects what our “bad” draws look like.

- For every 2 cyclers we play, it’s reasonable to cut 1 land. This trade isn’t free; sometimes we’ll have to cycle on early turns to find land.

-

The binomial coefficient \( { {n}\choose{k} } = \frac{ n! }{ k! \, (n-k)! }\) is the number of different ways to choose \(k\) elements from a list of length \(n\). For example, the number of possible 7-card hands from a 40-card deck is \( { {40}\choose{7} } = \frac{40!}{7! \, 33!}\), which comes out to 18.6 million. Going a step further, we can calculate the number of opening hands containing exactly 3 lands and 4 spells: \( { {23}\choose{4} }{ {17}\choose{3} }\), or 6.0 million, assuming 23 spells and 17 lands. By dividing the two, we find this deck will draw exactly 3 lands in its opening hand in about a third of all possible games. ↩

-

Some premier cards like Cast Out and Curator of Mysteries have the word “cycling” on them… but if we’re not willing to cycle them at the first opportunity, they don’t count as cyclers. ↩